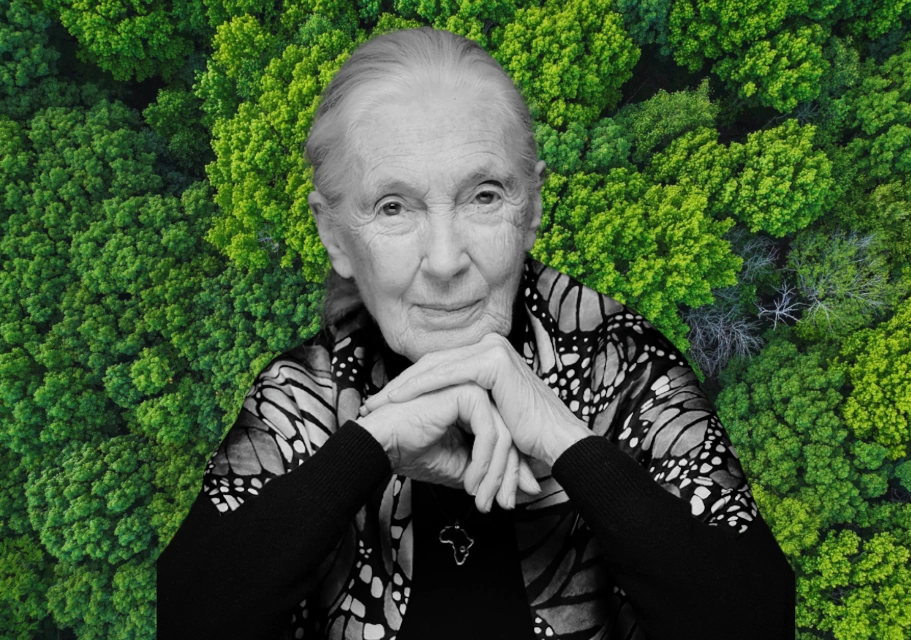

Recently we’ve been shifting Suave more into environmental work. Climate Week just passed in New York and Jane Goodall was there, still speaking for the earth. Now, only days following the NYC climate event, she has passed. This post is going to be longer than what we usually share, because it is both a tribute to her and a reflection on where we are headed. RIP Jane Goodall.

Jane’s Legacy

Jane Goodall’s life was extraordinary. In 1960 she arrived at Gombe in Tanzania and changed science forever. She showed the world that chimpanzees hunt, that they make and use tools, and that each one has a personality. When she described David Greybeard using a grass stem to fish termites, it shattered the barrier science had drawn between humans and other animals.

She did not stop with research. She founded the Jane Goodall Institute to continue community-centered conservation, and she launched Roots & Shoots, a program that empowers young people to start projects in their own neighborhoods.

“The least I can do is speak out for those who cannot speak for themselves.”

She carried that philosophy her entire life. She also warned:

“The greatest danger to our future is apathy.”

She knew people cared, but she also knew how easy it was to stay silent. Her work was proof that you do not need a lab coat to protect the earth. You need to notice, speak, and keep showing up.

What We Have Seen

I feel her lessons in the two places I know best: Staten Island and Pennsylvania.

In Staten Island, natural buffers once held back water. But in 2012 Hurricane Sandy arrived. At its peak it had been a Category 3 storm, and by the time it neared New Jersey it was still at Category 1 strength. Just before landfall it was reclassified as a post-tropical cyclone, but the winds and surge were still hurricane force. Sandy pushed a massive wall of water into Staten Island’s shores. Entire neighborhoods were flooded. Homes were destroyed. Dozens of lives were lost. It was one of the darkest moments in the borough’s history and it showed what happens when rising seas and powerful storms meet weakened landscapes.

Nine years later, Hurricane Ida delivered another kind of disaster. Ida had slammed into Louisiana as a Category 4 hurricane. By the time it reached the Northeast it had weakened and was reclassified as a post-tropical cyclone, but the rainfall was historic. In parts of New York City more than nine inches fell in less than twelve hours. Streets, basements, and parking lots turned into rivers. Thirteen people died in the city, many trapped in basement apartments. In Staten Island, families lost cars, basements were destroyed, and people were displaced.

Sandy and Ida together show the reality. One brought surge, the other rain, but both exposed the same weakness. Stronger storms and lost natural buffers combine to create tragedy.

In Pennsylvania, the story is different but connected. Heavy rains cut through farmland, sending soil, fertilizer, and chemicals into creeks, rivers, and streams. Banks collapse. Water turns brown. Towns downstream pay the price. The Susquehanna River drains almost half the state and carries about half the freshwater that enters the Chesapeake Bay, along with much of the nitrogen and phosphorus pollution the Bay struggles with.

I have walked along creeks after storms and seen them run orange from abandoned mine drainage, the legacy of coal seams cut open and left exposed. I have driven past hillsides where forests were cut too hard and the next rain peeled the soil right off. I have also stood by places where restoration crews planted riparian buffers only a few years earlier and already the banks hold firm, roots knit the soil, and the water runs clearer.

Both city and countryside are being pushed out of balance. Staten Island’s mistake is overbuilding. Pennsylvania’s mistake is extraction and neglect. Both are also facing the same pressure of overdevelopment. Talking with people across the East Coast, I keep hearing the same story: we are building too fast, ignoring habitats, and paying the price later.

Beyond Wetlands: All Habitats Matter

It is not just wetlands we are losing. Prairies, meadows, and forests are vanishing too, and the cost is showing up in new ways. Each of these landscapes is a kind of infrastructure. A prairie cools the ground and absorbs water. A meadow feeds pollinators and keeps soil from washing away. A forest creates shade, stores carbon, and keeps a neighborhood livable.

“You cannot save the forests without helping the people, and you cannot help the people without saving the forests.” – Jane Goodall

And then there are the fires. For centuries, old growth forests buffered fire. Big trees with thick bark and deep roots survived burns, stabilizing the forest for the next generation. But when those old giants were logged and replaced with uniform young growth, resilience was stripped away. New forests are thinner, drier, more homogenous, and when drought and heat rise, they burn hotter and faster.

Research in California’s sequoia groves shows the scale of loss: in high-severity fires, 84 percent of large sequoias died, a mortality rate almost unthinkable in forests once adapted to fire. Studies across temperate forests point to the same truth. Structural diversity, mixed ages, and intact legacy trees help moderate fire severity, while simplified young stands feed the flames. And in many western landscapes, regrowth is now failing altogether. Heat and dryness stop seedlings from reestablishing, leaving bare soil where forest once stood.

Meadows, forests, and prairies are not just scenery. They are fire buffers, storm buffers, and climate buffers. When they go, we lose protection we barely noticed we had.

Meanwhile, we have turned lawns into the default. The history goes back to English estates where a wide green lawn was a sign of wealth. It was proof you did not need to grow food on that land. In America it spread as a symbol of order and success. But lawns do not feed us. They do not cool like forests. They drink water. U.S. lawns consume nearly 9 billion gallons a day in summer. They guzzle chemicals and add heat.

By contrast, native plantings and permaculture landscapes perform like infrastructure. Deep-rooted prairie grasses can absorb up to six times more water than turf grass. Native gardens and canopy can reduce summer air temperatures by two to nine degrees Fahrenheit. A meadow of wildflowers can support more than twenty pollinator species, while a lawn often supports none. Wetlands can store more than a million gallons of stormwater per acre. And permaculture systems often produce two to four times the yield of conventional crops while building healthier soil.

In Staten Island and in cities everywhere, this is not just theory. Hot sidewalks and blacktop can run fifteen to twenty degrees hotter than nearby planted ground. A tree shading a sidewalk can cool the surface by ten to twenty degrees and lower the air around it. Planted corridors and rain gardens absorb stormwater that would otherwise overwhelm sewers. In the heat waves we know are coming, these differences will decide whether neighborhoods are livable.

A meadow or prairie planted with native flowers, grasses, and shrubs is not just beautiful. It is practical. It cools the ground, absorbs storms, and supports life. Lawns are an expense. Living habitats are assets.

Staten Island’s Call to Action

Staten Island already has a Greenbelt and a Bluebelt legacy. It could lead again. It could be known as the borough of resilience. Imagine more linked corridors, more restored marsh edges, more projects that weave solar, habitat, and data together.

Here’s where Suave fits. Our thermal and aerial data can show where resilience is holding and where it is breaking. We can highlight heat islands, pooling water, and stressed vegetation in ways that help communities plan smarter and avoid repeating the mistakes that made Sandy and Ida so costly.

If you are working on Staten Island, we want to connect. We can help document sites, track progress, and show the return on investment of nature-based solutions. Staten Island has the pieces. It just needs to keep leaning in.

Pennsylvania’s Call to Action

Pennsylvania has just as much to gain, maybe more. Its rivers feed the Chesapeake Bay. Its farmland feeds millions. Its hills and forests hold the headwaters of streams that cross the region.

But it also has scars: abandoned mines leaking orange water, eroded fields, towns flooding again and again. The Susquehanna is both lifeline and burden.

The solutions are already known. Riparian buffers, regenerative farming, wetland restoration, mine drainage treatment. These are not luxuries. They are survival. And they are cheaper than constant repairs. A dollar spent on buffers saves many more in flood damage. A restored wetland filters water for free compared to building treatment plants.

Here’s how we can help in PA. Our thermal imaging can capture slope instability, see pooling in fields, and track where creeks overflow. With clear aerial data, communities and farmers can make the case for grants, investments, and projects that save money long term.

If you are in Pennsylvania, we want to connect. From farmlands to creeks to rivers, we can help document and protect the systems that keep towns safe and land productive. Just like Staten Island, Pennsylvania can make resilience its identity.

Closing Reflection

Jane Goodall showed that one person with patience and persistence can reshape how the world thinks. She reminded us that we are part of the animal kingdom, that apathy is the greatest danger, and that every small step matters.

For me, every scan, every thermal map, every conversation with a landowner or a community group is one of those steps. From the Greenbelt in Staten Island to the farmlands and creeks and rivers in Pennsylvania, the work ahead is clear.

Jane warned us that apathy is the greatest danger. That is why we cannot stand still. Every scan, every partnership, every restored acre matters. From Staten Island’s neighborhoods to Pennsylvania’s watersheds, the work is here and now.

RIP Jane Goodall. Thank you for teaching us to pay attention, to act with respect, and to believe that damaged places can recover.

Sources

New York City. Hurricane Ida Disaster Recovery and Response. nyc.gov

NY1. Staten Island family still struggling to rebuild after Hurricane Ida. ny1.com

NOAA / NHC. Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Sandy (2012). nhc.noaa.gov

Wikipedia summary of Sandy in NY: Effects of Hurricane Sandy in New York

USDA Forest Service. Giant sequoia forests losing resilience to wildfires. fs.usda.gov

ScienceDirect. Forest structure moderates wildfire severity. sciencedirect.com

Fire Ecology Journal. Post-fire regeneration challenges. fireecology.springeropen.com

EPA. Nutrient pollution from the Susquehanna into the Chesapeake Bay. epa.gov

EPA. Outdoor Water Use in the United States. epa.gov

NOAA. Urban Heat Island Effect. climate.gov

US EPA. Using Trees and Vegetation to Reduce Urban Heat Islands. epa.gov

Tallgrass Prairie Center, UNI. Prairie Roots Study. tallgrassprairiecenter.org

Xerces Society. Pollinator Habitat in Yards and Gardens. xerces.org

Rodale Institute. Permaculture and Regenerative Agriculture Data. rodaleinstitute.org